Avicenna J Dent Res. 11(4):125-130.

doi: 10.34172/ajdr.2019.25

Original Article

An Evaluation of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices of Obstetricians and Midwives Concerning Oral Health of Pregnant Women in Birjand in 2019

Leili Alizadeh 1  , Elahe Allahyari 2, *

, Elahe Allahyari 2, *  , Farzane Khazaei 3

, Farzane Khazaei 3

Author information:

1Assistant Professor of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, School of Dentistry, Birjand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran.

2Assistant Professor of Biostatistics, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Health, Birjand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran.

3Student of Dentistry, Student Research Committee, Department of Dentistry, Birjand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran.

Abstract

Background: Periodontal disease in pregnant women usually occurs due to physiological changes during pregnancy and is associated with adverse prenatal and perinatal outcomes. However, pregnant women are reluctant to visit a dentist because of unreliable information or perceived hazards of dental procedures for the mother and fetus. Therefore, it is vital to examine the knowledge and practice of obstetricians and midwives and their attitude towards oral health of pregnant women as they are closely connected with these women.

Methods: In this study, 90 obstetricians and midwives from Birjand were randomly selected. The data for their knowledge, attitude, and practice were collected through self-report. The scale developed by Malek Mohammadi et al, with a high reliability of 80%, was used for data collection. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.0.

Results: Most of the participants (65.6%) worked in the hospital setting, and an average period of 10.32±8.24 years had passed from the subjects’ graduation. Of them, 82.2% provided care services for more than 40 hours per week for an average number of 31.3±67.6 patients. The mean score of knowledge, attitude, and practice were 6.27±1.33, 19.43±2.10, and 4.32±1.35, respectively. All participants considered it important to observe oral health during pregnancy, and 91.1% referred their patients to the dentist. Most of the participants (37.78%) obtained their information from continuous medical education programs.

Conclusions: The results of this survey showed that the attitude and practice of obstetricians and midwives were satisfactory given their level of knowledge about the importance of oral health during pregnancy. However, they were still far from standard guidelines. Therefore, it is recommended that their knowledge and skills should be increased to obtain optimal care during pregnancy.

Keywords: Knowledge, Attitude, Practice, Periodontal disease, oral health

Copyright and License Information

© 2019 The Author(s); Published by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium provided the original work is properly cited.

Citation: Alizadeh L, Allahyari E, Khazaei F. An Evaluation of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices of Obstetricians and Midwives Concerning Oral Health of Pregnant Women in Birjand in 2019 Avicenna J Dent Res. 2019;11(4):125-130. doi: 10.34172/ajdr.2019.25.

Background

Highlights

Oral diseases are among the most common diseases (1). The World Health Organization has recognized oral health as part of human public health, maintaining that untreated oral diseases have a profound effect on human quality of life (2). Although oral diseases threaten all population groups, some groups are more vulnerable than others due to specific physiological conditions. For example, while pregnancy is a normal process, physiological changes during this period, including increased oral acidity, morning nausea and vomiting, and gingivitis during pregnancy increase the risk of oral and dental diseases and associated injuries in the fetus (3). During pregnancy, periodontal diseases occur in various forms, such as pregnancy gingivitis, pyogenic granuloma (pregnancy tumor), and stomatitis (oral inflammation) (4).

Gingivitis occurs in half of the pregnant women and causes swelling, redness, bleeding, and sensitivity of the gums. Experts believe that gingival bleeding occurs during pregnancy due to hormonal changes and consider it necessary for the mother to reduce it through daily care and oral hygiene (3). Oral dysfunction can impair one’s dietary intake, the digestive system, and other systems of the body. For example, gum infections are potential sources of other injuries such as parotid gland infection, gastrointestinal and respiratory tract infections, heart disease, and rheumatoid arthritis (4). Many studies have shown that periodontal disease during pregnancy is associated with adverse prenatal outcomes including preeclampsia, preterm labor, low birth weight, neonatal admission, and obligatory hospitalization of the neonate in the neonatal intensive care unit (5).

Notwithstanding, some pregnant women fail to receive much preventive or restorative care because they believe that dental treatments can harm the fetus (6,7). Research has shown that 45% of women believe they should not have dental procedures during pregnancy (8). Moreover, 70% of women have a negative attitude to oral care during pregnancy due to inaccurate information and fear of the risks of dental procedures for the mother and the fetus (4). Nonetheless, except for dental x-rays (which can cause delivery of underweight newborns), other dental treatments do not pose a threat to the mother or the fetus (9).

Although pregnant women are somewhat aware of their oral health status, they refuse to go to the dentist because of inadequate knowledge. Proper education can improve the level of oral health among pregnant women (10). The knowledge and attitudes of obstetricians and midwives are significant contributors to the knowledge of pregnant mothers. As noted in a study by Wooten et al in 2011, only 62% of obstetricians and midwives screen their pregnant patients for oral diseases as part of their routine examination (11).

As most pregnant women refer to obstetricians and midwives and act on their recommendations earnestly, the knowledge of these healthcare providers about oral problems during pregnancy and the type of attitude and practice they have are critical. Providing effective collaboration between dentists and obstetricians and midwives can play a critical role in the prevention and control of many oral diseases in the mother and child. Additionally, by improving mothers’ knowledge and providing appropriate education, many oral and systemic disorders can be prevented (5). This study aimed to assess the knowledge, attitude, and practice of obstetricians and midwives regarding the oral health of pregnant women so that the way is paved for planning to improve the oral health of mothers and their children.

Materials and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted with 90 obstetricians and midwives from Birjand in 2019, who were selected via convenience sampling method. Initially, all midwives and obstetricians working in Birjand hospitals and healthcare centers were listed, of whom 90 individuals were selected randomly. Subsequently, they were invited to participate in the study by visiting their workplaces, including private or public clinics, health centers, hospitals, and offices. Participation in the study was voluntary, and the questionnaire was completed anonymously by the participants.

To obtain the desired information and results, the researchers completed a checklist, which covered the individual’s age, academic degree, place of employment, work experience, number of patients visited per week, number of years from graduation, and hours of work per week. We then used a questionnaire developed by Malek Mohammadi et al in 2016 (12). The questionnaire assessed knowledge (11 items), attitude (11 items), and practice (6 items) of obstetrics and midwives regarding oral health in pregnant women. The questionnaire reviews the sources of information the participants apply and evaluates one’s knowledge of oral health by posing questions such as “Do you think you need more information on oral care in pregnant women?”, “How do you evaluate your information about the importance of oral health in pregnant women?”, and “Have you ever visited a dentist yourself?” Correct answers in the knowledge domain are scored 1, and incorrect answers or no answers are scored 0. In the attitude domain, the items are scored on a three-point Likert scale (Correct answer = 2, Uncertainty = 1, and Incorrect answer = 0), and for the practice domain, the items are scored 1 for Yes and 0 for No. Therefore, the knowledge scores range from 0 to 11, attitude scores from 0 to 22, and practice scores from 0 to 6. The questionnaire has acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient = 80%). Results were reported as mean and percentage using SPSS version 22.0.

Results

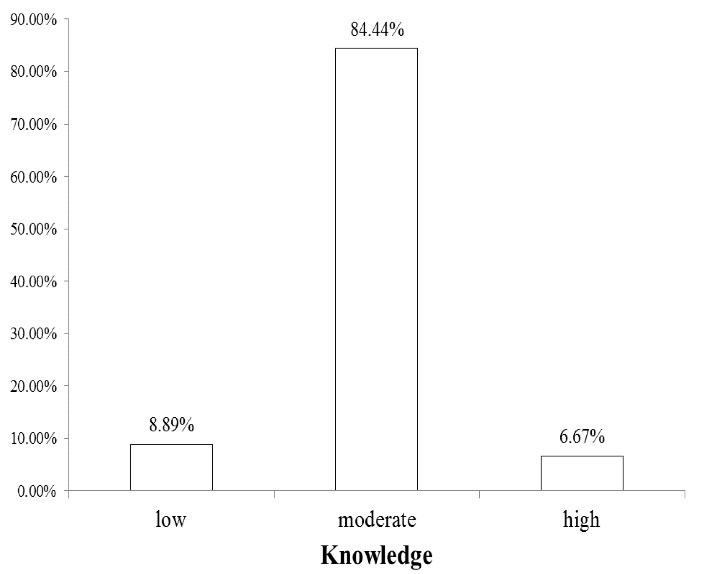

The present study was conducted with 90 obstetricians and midwives aged between 23 and 53 years. Two obstetricians (3.9%), 6 (6.7%) midwives with a master’s degree, and 82 (91.1%) midwives with a bachelor’s degree participated, of whom 59 (65.6%) worked in hospitals and 31 (34.4%) in health care centers. The mean number of years after graduation and work experience were 10.32 ± 8.24 and 9.79 ± 8.15 years, respectively. Of them, 82.2% (n=74) worked for more than 40 hours a week, and the average number of patients visited by them per week was 31.13 ± 67.6 patients (Table 1). The mean scores of knowledge, attitude, and practice were 6.27 ± 1.33, 19.43 ± 2.10, and 4.32 ± 1.35, respectively. According to the collected data, only 6 (6.67%) of the participants had a high knowledge score (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Studied Population

|

Variable

|

No. (%)

|

| Specialty |

|

| Obstetrician |

2 (2.2%) |

| Midwife (M.Sc.) |

6 (6.7%) |

| Midwife (B.Sc.) |

82 (91.1%) |

| Work location |

|

| Hospital |

59 (65.6%) |

| Health center |

31 (34.4%) |

| Working hours per week |

|

| 21-30 |

1 (1.1%) |

| 30-40 |

15 (16.7%) |

| >40 |

74 (82.2%) |

| Age |

33.79±8.20 |

| Years after graduation |

10.32±8.24 |

| Duration of practice |

9.79±8.15 |

| Number of patients visited per week |

31.13±67.6 |

* Data presented as mean ± SD.

Figure 1.

Evaluation of Knowledge in Studied Population.

.

Evaluation of Knowledge in Studied Population.

Table 2 summarizes the results of the attitude of the participants. It was revealed that 100% of the participants believed that oral hygiene was important during pregnancy. Besides, 96.7% believed that the referral of pregnant women with oral injuries to the dentist could play an essential role in maternal and fetal health and that the oral health of pregnant women is extremely important for their general health. Moreover, 93.3% considered dental care during pregnancy important to prevent preterm delivery. Additionally, 90% believed that pregnant women’s awareness of oral health had an impact on their child’s future health. Furthermore, 86.7% believed that it was necessary to refer pregnant women to the dentist. In addition, 84.4% agreed that nausea in pregnant women affected their dental health. Similarly, 81.1% agreed that tooth decay in the mother had an impact on fetal health. Moreover, 80% did not find dental treatment dangerous for pregnant women. When asked if they agreed with the statement “Gain a child, lose a tooth”, 61.1% disagreed, and 54.4% considered gingivitis caused by hormonal changes in pregnant women preventable.

Table 2.

Evaluation of Attitude in the Study Population.

|

|

Correct

No. (%)

|

Incorrect

No. (%)

|

Not Sure

No. (%)

|

| Tooth decay in the mother has an impact on fetal health. |

73 (81.1) |

9 (10) |

8 (8.9) |

| Dental care during pregnancy is essential to prevent preterm birth. |

84 (93.3) |

2 (2.2) |

4 (4.4) |

| Gingivitis caused by hormonal changes in pregnant women can be prevented. |

49 (54.4) |

19 (21.2) |

22 (24.4) |

| Referral of pregnant women with oral injuries to dentists can play an important role in maintaining maternal and fetal health. |

87 (96.7) |

1 (1.1) |

2 (2.2) |

| Oral health in pregnant women is highly important for their general health. |

87 (96.7) |

0 (0) |

3 (3.3) |

| Pregnant women’s awareness of oral health affects their child’s health in the future. |

81 (90) |

2 (2.2) |

7 (7.8) |

| It is obligatory to refer pregnant women to the dentist. |

78 (86.7) |

5 (5.6) |

7 (7.8) |

| Dental treatments are dangerous for pregnant women. |

72 (80) |

7 (7.8) |

11 (12.2) |

| It is important to observe oral health during pregnancy. |

90 (100) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Nausea in pregnant women affects their dental health. |

76 (84.4) |

8 (8.9) |

6 (6.7) |

| What do you think about the famous saying, "Gain a child, and lose a tooth"? |

55 (61.1) |

20 (22.2) |

15 (16.7) |

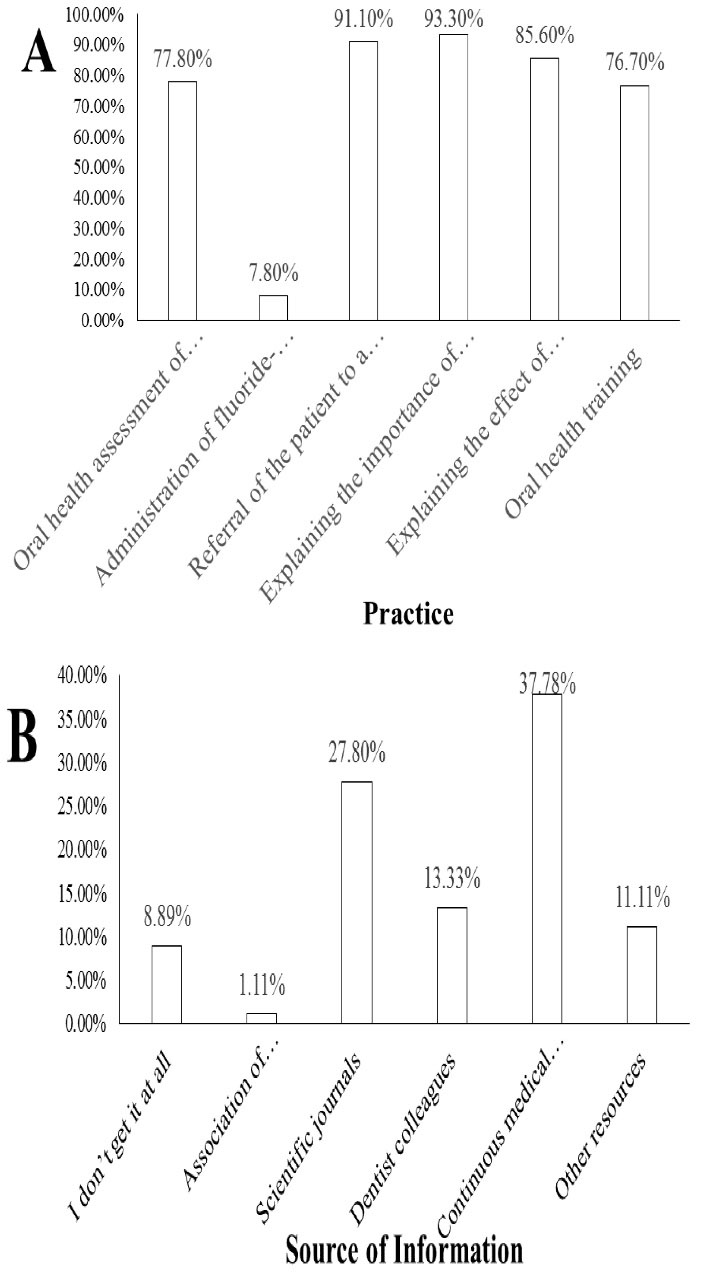

The results of the practice of the participants concerning oral health in pregnant women are displayed in Figure 2A. Of the participants, 93.3% and 85.6%, respectively, emphasized the importance of health during pregnancy and its impact on the health of the child. While 76.7% provided specific advice on oral hygiene and 77.8% screened their clients for oral health, 91.1% reported referring their patients to a dentist. Besides, mouthwash was administered in only 7.8% of cases. Figure 2B depicts the oral health information resources of the participants, with the highest percentage (37.78) belonging to continuous medical education and the lowest (1.11) to the Gynecologists and Obstetricians Association.

Figure 2.

(A) Percentage of Correct Answers in Each Practice Question. (B) Percentage of Source of Information in Study Population.

.

(A) Percentage of Correct Answers in Each Practice Question. (B) Percentage of Source of Information in Study Population.

The results for the items 2 to 4 are presented in Table 3. A total of 88 (97.8%) individuals stated that they needed more information about oral care in pregnant women. Fifty (55.6%) evaluated their knowledge of the importance of oral health in pregnant women as insufficient. Of those surveyed, 3 (3.3%) had never referred to a dentist, 62 (68.9%) referred to a dentist if they faced a problem, and 25 (27.8%) referred for regular examinations.

Table 3.

Evaluation of Oral Health Knowledge from the Participants’ Perspective

|

Do you think you need more information about oral care in pregnant women?

|

|

| Yes |

88 (97.8) |

| No |

2 (2.2) |

|

How do you evaluate your knowledge of the significance of oral health in pregnant women?

|

|

| Not enough |

50 (55.6) |

| Enough |

40 (44.4) |

|

On what occasions do you visit a dentist yourself?

|

|

| Never |

3 (3.3) |

| Regular checkup |

25 (27.8) |

| Problem occurred |

62 (68.9) |

Discussion

In the present study, most of the participants had a moderate level of knowledge, and the mean knowledge score was 6.27 ± 1.33. In a study conducted by George et al on midwives’ knowledge of oral health care during pregnancy, a large number of the participants were unaware of the significance of oral health in pregnancy, and their ignorance of the associated impacts on the mother and child prevented them from discussing the importance of oral hygiene and dental visits with their patients (13). The results of a study conducted by George et al were inconsistent with those of the present study in that our participants reported a higher level of knowledge. The results of studies by Roshandel and Malek Mohammadi, which aimed at assessing the knowledge, attitude, and practice of gynecologists and midwives, were consistent with the results of the present study in which the mean score of participants’ knowledge was at a moderate level (12,14). No significant relationship was found between the years after graduation and the knowledge score in the present study. Therefore, it can be assumed that work experience or more recent education may not necessarily lead to an increase in the level of knowledge, which is consistent with a study conducted by Roshandel in Tabriz (14).

In the present study, 87.77% of participants were aware of the association between periodontal disease and the risks of preterm birth or low birth weight. In this regard, our results were better than those of a study by Zanata et al (15). Moreover, 74.5% of those in Strafford and colleagues’ study believed that preterm labor and low birth weight were associated with poor oral health (16), which was not significantly different from the present study. Additionally, 60% of the study population in da Rocha and colleagues’ study attributed preterm birth and low birth weight to periodontal disease with certainty (17). In Wooten’s study, 90% of the participants considered these diseases as risk factors for pregnancy complications (11).

One critical factor that leads pregnant women to refuse to receive dental services and treatments is their fear of adverse effects on their babies. Nevertheless, the required dental treatments (such as acute infections or severe caries) have been proven to be quite safe during pregnancy. Obstetricians and midwives should be aware of such issues and need to reassure pregnant women of these issues. In the present study, 80% of people found it safe to have dental treatments during pregnancy (for which the second trimester is proposed as the appropriate time). The study by Rhodus showed that many physicians and dentists consider dental and pharmacological treatments dangerous during pregnancy and that they are reluctant to provide treatment to these patients (18), which was inconsistent with the present study. In the current study, 90% of the study population reported the second trimester as the best time for dental treatment, which corresponds with a study conducted by Zanata et al in Brazil (15). In a study by Strafford et al, however, 66% of obstetricians stated that dental operations are feasible in all trimesters (16). In the present study, 41.11% of the participants considered lidocaine plus vasoconstrictors permissible for pregnant women, which is higher than the rates reported by Zanata et al (16.5%) and lower than that reported by Strafford et al (99%) (16).

Concerning the practice dimension, 65% of obstetricians believed that pregnant women should be examined for oral health during the first trimester of pregnancy, which corresponds with the rate reported by Strafford et al (16). Moreover, 77.8% of the participants screened their clients for oral health. In Strafford and colleagues’ study, although 64% of obstetricians believed that screening for oral diseases and mouth examination should be a part of pregnancy examinations, only 49% of them evaluated their clients for oral health (16). In Wilder and colleagues’ study, only 22% of obstetricians assessed their clients for oral health, and 51% recommended dental appointments during pregnancy (19).

Contrary to the current study, where 61% of the participants rejected the generally-held belief “Gain a child, lose a tooth”, many participants in studies done by Rocha et al and Golkari et al agreed with this statement (17,20). However, such a statement clearly indicates the interplay between systemic conditions during pregnancy and oral health. The findings of this study showed that 22.2% of participants were in favor of tooth loss during pregnancy, 16.7% were uncertain, and 61.1% were against tooth loss during pregnancy. These findings correspond with the results of a study by Wilder et al, where 28% of obstetricians stated that tooth loss may or may not occur during pregnancy, 19% were not sure, and 53% believed that tooth loss would occur or would probably occur (19). In terms of practice, 76.7% of the participants in this study provided oral health education for their patients, compared to only 20% in the study by Wooten et al (11). Moreover, 77.8% of the participants considered oral health as a part of prenatal care, while in a study conducted by Patil et al, the rate amounted to 94% (21).

In the present study, more than 86% of the participants agreed with referring pregnant women suffering from dental injuries to the dentist to ensure maternal and fetal health, and 91% of the participants referred their patients to the dentist. According to George et al, very few midwives specifically discussed oral health with their patients for the reason that appropriate referral routes for pregnant women in need of dental treatment were unclear (13). According to Kloetzel et al, only 40% of pregnant women were referred to the dentist by their midwife (22), which is lower than the reported referral rate in the present study. Therefore, the barriers mentioned in other studies appear to be less severe in the present study. Based on the results obtained by Rocha et al, 88% of obstetricians referred their patients to the dentist for oral health-related issues (17). According to Wooten et al, 86% of the respondents reported referring their patients to the dentist during the past year (11), which was consistent with the present study. In the study by Patil et al, although 70% of the participants agreed with referring pregnant women for dentistry services, only a small number of patients were referred. The reasons lie in high costs, cultural beliefs, and restricted access to treatment (21).

Referral to the dentist is of particular importance when the patient has oral health problems. The necessity will be determined through examination. In the present study, 77.8% of the participants were examined and screened for oral health, which was a higher rate compared to a study by Golkari et al (62%) (20). In the study by Wooten et al, 62% of midwives performed the ophthalmologic examination on their patients (11), and according to the Patil et al, 60% of obstetricians agreed with regular oral examinations, and 75% did so if the patient complained (21), which do not correspond with the present study. The relatively higher number of examinations done by the participants in this study may be attributed to their higher level of knowledge about oral problems and related complications. Besides, more than 54% of those surveyed confirmed that gum problems caused by hormonal changes during pregnancy are preventable. Besides, 93% believed that dental care during pregnancy can affect low birth weight and preterm births.

In the present study, only 7.8% of the participants prescribed fluoride mouthwash for their clients. Since it is the dentists’ responsibility to determine the proper time to administer this mouthwash, patients should be referred to dentists in this regard. In the present study, about 37% of the participants described continuous education courses as a source of up-to-date information on the impact of oral health on the general health of pregnant women, indicating the need for these programs. Furthermore, 55% of the respondents found their knowledge about the oral health of pregnant women to be inadequate, and 97% underlined the need for further education, which is in line with the rate reported by Wooten et al (11). Therefore, there is a need for specific and pre-defined training for specialists and midwives. The higher level of attention paid to the oral health of pregnant women in the present study than in other studies can be attributed to the respondents’ own use of dental treatments, because the results of this study indicated that more than 96% of the participants had already received dental services themselves, as opposed to a study by Golkari et al where only one-third of the participants had at least one dental visit (20).

Conclusions

Given the fact that obstetricians and midwives are referred to as dental health assistants in dentistry resources (12), the practice level of individuals was generally appropriate as compared with their knowledge. Closer professional collaboration between dentists and obstetricians and midwives seems to play a major role in promoting people’s health. Moreover, the incorporation of programs that can promote closer interaction between oral health and the general health system can enhance the practice of obstetricians and midwives.

References

- Mazlumi MS, Ruhani TN. The study of factors related to oral self-care with Health Belief Model in Yazds’ high school students. Journal of Birjand University of Medical Sciences 1999; 3:40-8. [ Google Scholar]

- Emami Moghadam Z, Ajami B, Behnam Vashani HR, Sardarabady F. Perceived benefits based on the health belief model in oral health related behaviors in pregnant women, Mashhad, 2012. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil 2013; 16(44):21-7. doi: 10.22038/ijogi.2013.654 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Radnai M, Gorzó I, Nagy E, Urbán E, Eller J, Novák T. [Caries and periodontal state of pregnant women Part I Caries status]. Fogorv Sz 2005; 98(2):53-7. [ Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA. Carranza’S Clinical Periodontology. China: Saunders; 2006.

- Han YW, Redline RW, Li M, Yin L, Hill GB, McCormick TS. Fusobacterium nucleatum induces premature and term stillbirths in pregnant mice: implication of oral bacteria in preterm birth. Infect Immun 2004; 72(4):2272-9. doi: 10.1128/iai.72.4.2272-2279.2004 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Haji Kazemi E, Hossein Mohseni SH, Oskouie SF, Haghani H. The association between knowledge, attitude and performance in pregnant women toward dental hygiene during pregnancy. Iran Journal of Nursing 2005; 18(43):31-8. [ Google Scholar]

- Bahri N, Iliati HR, Bahri N, Sajjadi M, Boloochi T. Effects of oral and dental health education program on knowledge, attitude and short-time practice of pregnant women (Mashhad-Iran). Journal of Mashhad Dental School 2012; 36(1):1-12. doi: 10.22038/jmds.2012.831.[Persian] [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gaffield ML, Gilbert BJ, Malvitz DM, Romaguera R. Oral health during pregnancy: an analysis of information collected by the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. J Am Dent Assoc 2001; 132(7):1009-16. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0306 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Gilbert BC, Shulman HB, Fischer LA, Rogers MM. The Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS): methods and 1996 response rates from 11 states. Matern Child Health J 1999; 3(4):199-209. doi: 10.1023/a:1022325421844 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Al-Tamimi S, Petersen PE. Oral health situation of schoolchildren, mothers and schoolteachers in Saudi Arabia. Int Dent J 1998; 48(3):180-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.1998.tb00475.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Wooten KT, Lee J, Jared H, Boggess K, Wilder RS. Nurse practitioner’s and certified nurse midwives’ knowledge, opinions and practice behaviors regarding periodontal disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes. J Dent Hyg 2011; 85(2):122-31. [ Google Scholar]

- Malek Mohammadi T, Malek Mohammadi M. Knowledge, attitude and practice of gynecologists and midwifes toward oral health in pregnant women in Kerman (2016). Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil 2017; 20(4):9-18. doi: 10.22038/ijogi.2017.8976.[Persian] [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- George A, Johnson M, Duff M, Blinkhorn A, Ajwani S, Bhole S. Maintaining oral health during pregnancy: perceptions of midwives in Southwest Sydney. Collegian 2011; 18(2):71-9. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2010.10.003 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Roshandel M. Evaluation of knowledge level of gynecologists in Tabriz concerning the association between periodontal disease during pregnancy and preterm infants with low birth weight. Thesis. Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.

- Zanata RL, Fernandes KB, Navarro PS. Prenatal dental care: evaluation of professional knowledge of obstetricians and dentists in the cities of Londrina/PR and Bauru/SP, Brazil, 2004. J Appl Oral Sci 2008; 16(3):194-200. doi: 10.1590/s1678-77572008000300006 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Strafford KE, Shellhaas C, Hade EM. Provider and patient perceptions about dental care during pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2008; 21(1):63-71. doi: 10.1080/14767050701796681 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- da Rocha JM, Chaves VR, Urbanetz AA, dos Santos Baldissera R, Rösing CK. Obstetricians’ knowledge of periodontal disease as a potential risk factor for preterm delivery and low birth weight. Braz Oral Res 2011; 25(3):248-54. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242011000300010 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Rhodus NL. Oral health and systemic health. Minn Med 2005; 88(8):46-8. [ Google Scholar]

- Wilder R, Robinson C, Jared HL, Lieff S, Boggess K. Obstetricians’ knowledge and practice behaviors concerning periodontal health and preterm delivery and low birth weight. J Dent Hyg 2007; 81(4):81. [ Google Scholar]

- Golkari A, Khosropanah H, Saadati F. Evaluation of knowledge and practice behaviours of a group of Iranian obstetricians, general practitioners, and midwives, regarding periodontal disease and its effect on the pregnancy outcome. J Public Health Res 2013; 2(2):e15. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2013.e15 [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]

- Patil S, Thakur R, K M, Paul ST, Gadicherla P. Oral Health Coalition: Knowledge, Attitude, Practice Behaviours among Gynaecologists and Dental Practitioners. J Int Oral Health 2013; 5(1):8-15. [ Google Scholar]

- Kloetzel MK, Huebner CE, Milgrom P, Littell CT, Eggertsson H. Oral health in pregnancy: educational needs of dental professionals and office staff. J Public Health Dent 2012; 72(4):279-286. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2012.00333.x [Crossref] [ Google Scholar]